Thursday, July 5, 2012

Some Thoughts on Freedom, 7/4/2012

As I write this my country's 236th birthday is coming to a close. We had family and friends over to our home today to celebrate and spend time together. I put up our flag early this morning and was gratified as I looked up and down our street to see several U.S. flags waving in the breeze. It has been a good day.

And, yes, I'm a patriot. Maybe patriotism has lost some of its appeal, and maybe some people think it's corny to get a little teary eyed when the flag passes by or when a group of school children sing "The Star Spangled Banner." Maybe words like liberty and freedom and justice don't stir people the way they used to. But I still thrill to those things because those words still mean something to me. And I believe that aren't exclusively American.

Those men who nailed it all down for us back there in the beginning were expressing a vision that extended to all people everywhere. The patriotic pride I feel in being an American and in my country comes from my belief that our nation is the Olympus of liberty, the keeper of the flame of freedom for all people.

So, when I fly the flag on special holidays like today, or when I sometimes run it up just for the joy of seeing it against the blue sky, I'm saying more than "God bless America." I'm saying, "God bless all people everywhere who love the idea freedom and the principles that my country was founded on."

I remember Moses' great words, "Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof." And I'm remembering those people throughout my life, and those who came before me, who made it all possible in this blessed land of liberty and freedom.

I hope you all had a wonderful Fourth of July today and that you took a minute or two to express thanks for the blessings of freedom.

And, yes, I'm a patriot. Maybe patriotism has lost some of its appeal, and maybe some people think it's corny to get a little teary eyed when the flag passes by or when a group of school children sing "The Star Spangled Banner." Maybe words like liberty and freedom and justice don't stir people the way they used to. But I still thrill to those things because those words still mean something to me. And I believe that aren't exclusively American.

Those men who nailed it all down for us back there in the beginning were expressing a vision that extended to all people everywhere. The patriotic pride I feel in being an American and in my country comes from my belief that our nation is the Olympus of liberty, the keeper of the flame of freedom for all people.

So, when I fly the flag on special holidays like today, or when I sometimes run it up just for the joy of seeing it against the blue sky, I'm saying more than "God bless America." I'm saying, "God bless all people everywhere who love the idea freedom and the principles that my country was founded on."

I remember Moses' great words, "Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof." And I'm remembering those people throughout my life, and those who came before me, who made it all possible in this blessed land of liberty and freedom.

I hope you all had a wonderful Fourth of July today and that you took a minute or two to express thanks for the blessings of freedom.

Saturday, June 30, 2012

Read great reviews from our "Charlie's Girl" blog tour

June 13 Geo Librarian

June 16 For the Love of Books

June 22 So Simply Sara

June 24 Book Haven Extraordinaire

http://cedarfortbooks.com/blog-tour-charlies-girl/

To access reviews scroll down to see calendar and click on each of these individual dated entries shown above.

Wednesday, June 13, 2012

Henderson/St.George

I’m finally getting back on my feet after a long, exhausting

trip last week to sign books in the Las Vegas area (Henderson, to be exact) and

St. George, Utah. We met so many warm, friendly, and wonderful people I can’t

count them. The managers of the bookstores were not only helpful; they were

engaged and very supportive. Everyone who came by our table was friendly and

interesting, whether or not they bought a copy of Charlie’s Girl.

I’m finally getting back on my feet after a long, exhausting

trip last week to sign books in the Las Vegas area (Henderson, to be exact) and

St. George, Utah. We met so many warm, friendly, and wonderful people I can’t

count them. The managers of the bookstores were not only helpful; they were

engaged and very supportive. Everyone who came by our table was friendly and

interesting, whether or not they bought a copy of Charlie’s Girl.

By the way, if you live in the Las Vegas or St. George areas

and would like to buy a copy of Charlie’s

Girl, we signed several books for sale in these stores. Some folks do like

to have autographed copies, and we’re only too happy to oblige if possible.

Another feature of our trip was a visit with two former

missionary companions from long ago. Dean Swensen came down to St. George,

where two of his children live with their families, and Sylvan Turnblom and his

daughter, Jennifer, drove down from their home in Centerville. Sylvan and I had

not seen each other for over 40 years. What a reunion! I told Syl and Dean that

the visit was interesting because we could see who had gained the most weight

and lost the most hair. I won on both counts.

We also had the chance to spend some time in Las Vegas with

our nephew, Rob Danner, and his daughter, Sarah. We were expecting to see Rob,

but were surprised when Sarah walked into the bookstore with her

characteristically beautiful smile. It took a moment or two to recognize her.

Something about being outside your “natural habitat” I guess. We had dinner

together and then Rob put us up for the night.

Today begins our blog tour. It will go on for two weeks.

Several bloggers who love books will review Charlie’s

Girl. This blog tour is a great idea and will introduce the book to more

people than we would be able to reach otherwise. There are so many more

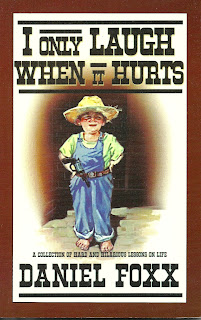

supportive people willing to help authors than when my first book (I Only Laugh When It Hurts) was

published way back when. I’m gratified to know that there are so many book

lovers out there.

Well, it’s good to be back home. Now back to the sequels to Charlie’s Girl.

Monday, June 4, 2012

Local husband and wife team publish latest novel - Peoriatimes.com: Entertainment

Local husband and wife team publish latest novel - Peoriatimes.com: Entertainment: Husband and wife writers Mary-Helen and Daniel Foxx announce the release of their new book, “Charlie’s Girl,” now available online on amazon.c…

Monday, May 28, 2012

German POW camp Christmas Day 1944

This is a rare photo taken in a German POW camp on Christmas Day 1944. The three men in the foreground are members of the American 82nd Airborne Division. The men in the background are French prisoners who had been captured in 1940. The soldier lying on the cot, covered by a blanket, is my uncle George Augustine "Auggie" Harris. Their German captors apparently tried to make the day as special as possible. You can see some beer bottles in the picture. Auggie was liberated by British troops on April 27, 1945.

Memorial Day is for remembering those who gave their lives in the service of our country. God bless them all and their families. I am grateful for them all. I am grateful for all those who sacrificed their lives in every war our country has fought from the beginning until now.

There is another group of American war veterans who came close to losing their lives in battle. They came home with broken bodies and tortured minds. Many died from their wounds after their wars had ended; sometimes long after. And I am grateful for them and their sacrifices.

This is a tribute to one of these, my uncle George Augustine Harris. He served with the 401st Glider Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division and faced his first combat during the invasion of Normandy which began on June 6, 1944--D-Day. His unit was pulled back to England after several weeks to prepare for the invasion of the Netherlands on September 17, 1944. This was the infamous "short cut to victory" campaign envisioned by Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

The invasion of the Netherlands was a two-part operation that, according to Montgomery, was to cross the Rhine and end the war with Germany by Christmas 1944. It was officially called Operation Market Garden and called for the 1st Allied Airborne Army, consisting of the British 1st Airborne Division and the American 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, to lay an airborne "carpet" which would take a series of bridges across rivers and canals between Belgium and the Rhine. The airborne troops would hold the bridges until a British armored army could race across the water obstacles, eventually crossing the Rhine and spreading out across the German industrial area of the Ruhr and force Germany to sue for peace.

It must have looked good on paper, because the allied high command agreed to launch Market Garden. Unfortunately, many a battle plan goes out the window when the bullets begin to fly. What looked like an easy walk through Holland for the Allies at the beginning of September had changed drastically by September 17 when the operation began. Two German armored SS divisions had been sent into the area days before and the Allied airborne divisions were dropped right on top of them.

After several days of desperate fighting the Allies had to pull back. Both the British and American airborne divisions suffered heavy losses, especially the British who had gone for the bridge across the Rhine at Arnhem--the famous "bridge too far."

My uncle, we all called him Auggie, was wounded by artillery fire near Ninjmegen on September 30, and captured. He would spend the rest of the war in a German POW camp. He nearly lost lost his leg, and did lose part of his left foot. For the rest of his short life (he died in December, 1952, at the age of 35) he walked with a limp, never having fully recovered from his wounds.

Today I pay grateful tribute to all those who lie in hundreds of military cemeteries around the world; and to those whose bones still remain unidentified in jungles, deserts, and fields. Over the years many observers have asked the question, "Where do we get such men?" The short answer is that they are fathers, and sons, and brothers, and uncles like Auggie. And yes, many women have made the same sacrifices. All for us. For our freedom. Let us never forget them.

Friday, May 18, 2012

My Other Books

Reissued by Pelican Publishing Co., Gretna, Louisiana 2009

If you've ever laughed to keep from crying; if you've ever felt that being grown up isn't all it's cracked up to be and found yourself bemused and confused by adulthood and parental responsibility; If you can remember what it was like to be a kid and have all the time in the world to do that all-important nothin'--then this book is for you, and you'll laugh when it hurts, too.

This unforgettable series of essays paints a bittersweet and vivid portrait of American life and of the lessons--some hard, some hilarious--life can teach. Looking back, Foxx relays his insights in relation to his coming of age and beyond. From the death of his father to the challenge of raising four sons of his own, he searches not only for understanding, but also for levity. As part of the growth process, Foxx passes his hard-won wisdom on to his children, with a touch of humor to ease the growing pains.

Available at

www.pelicanpub.com

www.amazon.com

Coauthored with Eddy W. Davison, former student and colleague

AWARDS

Arizona Book Award for Biography 2008

Finalist for 2008 Independent Book Publishers Association Benjamin Franklin Award

"Recommended as must reading for those who want to know Forrest and his way of war."

--Edwin C. Bearss, historian emeritus, National Park Service

"Chasing a figure such as Nathan Bedford Forrest through history is no easy task. Eddy Davison and Daniel Foxx have done so with the dedication and resolve of Old Bedford himself, creating along the way a rousing portrait of the soldier and the man."

--Brian S. Wills, Asbury Professor of History, University of Virginia

"The search for the truth . . . continues here with additional sources and analysis building upon the well-known legend of the Wizard of the Saddle."

--Lee Millar, president, General Nathan Bedford Forrest Historical Society

"Very enlightening as to Forrest's early years and his coming of age in the Civil War."

--Dean Becraft, past president, Scottsdale Civil War Roundtable

Eddy W. Davison teaches criminal justice at the International Institute of the Americas in Phoenix, Arizona, and serves as an adjunct professor of history at Ottawa University. He frequently writes and presents seminars on Civil War topics.

Daniel Foxx is professor of history emeritus at Ottawa University in Phoenix and has held past history teaching appointments at East Carolina University and Glendale Community College.

Sunday, May 13, 2012

MOTHERS DAY THOUGHTS

This weekend is Mothers Day. All over America sons and daughters will pay tribute and express their love to their mothers, as I do also. Unfortunately my mother died too soon at the age of sixty-two almost forty-five years ago. I was clear across the country attending college when it happened and still regret that I wasn't there to tell her how much I loved her and appreciated all she had done for me.

One of my favorite authors, Lewis Grizzard, wrote a little book about his love for his mother, "Don't Forget To Call Your Mama, I Wish I Could Call Call Mine." I'm sure all of us who have lost our mothers can relate to the sentiment of that title. So, if your mother lives close enough for you to visit, go see her. If not, pick up the phone and call. One day, sooner than you think, she will be gone. Don't let that happen without taking the opportunity to say a proper goodbye. You don't want to carry around for the rest of your life a bunch of "if onlys" and sad regrets.

My friend, Lara Lazenby, said it as well as it can be said on her Facebook page this morning, and I hope she doesn't mind my quoting her: "The hardest day of the year for those who have lost a mother, never had a mother, had a horrible mother, lost a child, or never had one. And harder still for all the mothers who are unappreciated by their thoughtless kids and spouses, left alone, abandoned or forgotten. And let's not forget the single moms, the superheroes, who do it alone every single relentless day of the year. And if I forgot someone . . . well, then I've totally made my point. Big heart hugs to you all!"

May I just add, as one who was fortunate to have such a wonderful mother: Say on, Sister Lara. God bless all mothers everywhere. And don't forget to call your mother. I wish I could call mine.

This weekend is Mothers Day. All over America sons and daughters will pay tribute and express their love to their mothers, as I do also. Unfortunately my mother died too soon at the age of sixty-two almost forty-five years ago. I was clear across the country attending college when it happened and still regret that I wasn't there to tell her how much I loved her and appreciated all she had done for me.

One of my favorite authors, Lewis Grizzard, wrote a little book about his love for his mother, "Don't Forget To Call Your Mama, I Wish I Could Call Call Mine." I'm sure all of us who have lost our mothers can relate to the sentiment of that title. So, if your mother lives close enough for you to visit, go see her. If not, pick up the phone and call. One day, sooner than you think, she will be gone. Don't let that happen without taking the opportunity to say a proper goodbye. You don't want to carry around for the rest of your life a bunch of "if onlys" and sad regrets.

My friend, Lara Lazenby, said it as well as it can be said on her Facebook page this morning, and I hope she doesn't mind my quoting her: "The hardest day of the year for those who have lost a mother, never had a mother, had a horrible mother, lost a child, or never had one. And harder still for all the mothers who are unappreciated by their thoughtless kids and spouses, left alone, abandoned or forgotten. And let's not forget the single moms, the superheroes, who do it alone every single relentless day of the year. And if I forgot someone . . . well, then I've totally made my point. Big heart hugs to you all!"

May I just add, as one who was fortunate to have such a wonderful mother: Say on, Sister Lara. God bless all mothers everywhere. And don't forget to call your mother. I wish I could call mine.

Saturday, May 5, 2012

FIGHTER JOCK WANNABE

I'm just a fighter jock wannabe

But I'm so old I know I'm never gonna be.

My old A2 hangs in the closet there

Languishing for want of wear.

I no longer look anything like dashing,

And only in highway's traffic face fears of crashing.

But my wannabe pilot's heart stays strong,

And stirs each time I hear an airplane's song.

I may have missed my chance on this side of the sunset,

But out there where the old pilots live on, I'll bet

The chance to fly awaits me yet.

[An "A2" is a leather flight jacket worn by military pilots during World War II, and still issued to Air Force pilots today.]

--Mary-Helen is the poet in the family (see her blog: http://ourwaywithwords.blogspot.com), but sometimes I try.

But I'm so old I know I'm never gonna be.

My old A2 hangs in the closet there

Languishing for want of wear.

I no longer look anything like dashing,

And only in highway's traffic face fears of crashing.

But my wannabe pilot's heart stays strong,

And stirs each time I hear an airplane's song.

I may have missed my chance on this side of the sunset,

But out there where the old pilots live on, I'll bet

The chance to fly awaits me yet.

[An "A2" is a leather flight jacket worn by military pilots during World War II, and still issued to Air Force pilots today.]

--Mary-Helen is the poet in the family (see her blog: http://ourwaywithwords.blogspot.com), but sometimes I try.

Tuesday, May 1, 2012

Reading Through Your Own Experience

READING THROUGH YOUR OWN EXPERIENCE

Someone asked me once what I meant by a certain passage I had written in one of my books. I appreciated that she had read my book thoughtfully, but the question made me uncomfortable. "What do you think it means?" I asked.

She gave a thoughtful answer and asked, "Am I right?"

I smiled and nodded, but I'm still not sure if that's what I really meant. Over the years since that encounter I've often wondered what I meant by a lot of things I've written. Here's what I've come to believe: I don't want to tell you what I mean. I want you to understand what it means to you, my reader.

When I was a kid in school I loved to read. I read almost everything from westerns to history to adventure. I even read the cereal boxes and can labels. In school I always read the literature assignments and had another book or two I was reading at the same time, but I was turned off when it came to class discussions on our reading assignments. They almost always consisted of questions like, "What does the author mean by such and so?" Or "Who are the 'dark watchers' in Hemingway's story?"

It wasn't that I didn't know what those things meant to ME, but how could I know what the author meant? I think she had written her story and invited me to understand it through my own experience.

Only once did I try to answer one of these questions from the teacher. We were reading poetry. "Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old Father Time is flying. . ." I was a young high school junior, and I knew what that meant to me. "For the sword outlasts the sheath," Byron wrote. Those lines invited me to look across the years to that time when the bodies of my sap-green classmates and I would age and prevent us from doing those things we took for granted at the age of seventeen.

"What do you think the author means by that line, 'For the sword outlasts the sheath?'" our teacher asked. When she looked me in the eye and called my name, I told her what I thought. Luckily I minced a lot of words and didn't thoroughly embarrass myself. And even now, liberated by age and a much more open society, that's all I'm going to say.

Literature teachers still nag their students to read authors' minds with that question, "What does the author mean by thus and so?" To that question I still have that same sense of discomfort when asked what I meant by something I had written. I think I'm uncomfortable because the real question is "What does this mean to you?"

Several years ago I attended a weekend conference of Southwest History teachers. We had read Edward Abbey's book, "The Brave Cowboy," in preparation for watching the Hollywood film version called "Lonely Are the Brave," and discussing the film and the book throughout the day. I'm a fan of Abbey's work and the film version as well. At the end of the story the cowboy is lying injured by the side of the road after he and his horse had been hit by a semi truck.

A discussion ensued after watching the movie in our morning session. Most of us agreed that the cowboy probably died. After all, he had just been slammed into by a semi truck traveling at a high rate of speed. But one of the professors in our group began to dominate the discussion. He identified himself as an expert on Abbey's work, and announced confidently that the cowboy had not died because he appears later in another of Abbey's books.

After lunch we reassembled to discuss the book when who walked in but Edward Abbey himself. "I was over in Scottsdale and heard that you're discussing my favorite author. Do you mind if I sit in?" Of course we didn't mind; we were happy to have him.

Our Edward Abbey expert lost no time in confronting Abbey with the question of the cowboy's survival. Maybe he wanted Abbey to agree with him. "Ed, I've read all your work," he said, "and I believe that the cowboy did not die. So my question to you, Ed, is did the cowboy, in fact, die at the end of the story?"

Abbey gave him a forty-yard stare for a moment or two and said, "Damned if I know."

Thursday, April 12, 2012

Demonstrators

I don't know about you, but the more demonstrators I see in the streets, the harder it is for me to take them seriously. That doesn't mean that THEY don't want to be taken seriously. In fact, you get the impression that a lot of them would sooner tear down the country to make a point--even if they don't know what their point is. There are few things more dangerous, and frightening, than hordes of seemingly mindless people roaming the streets destroying property and chanting angry slogans.

I realize that all citizens have a right under the First Amendment to demonstrate, protest, march, and otherwise express their views in a peaceable and lawful manner. I support that. But sometimes I wonder if we haven't become such a nation of grumblers over everything with which we disagree that the change we think we're demanding is lost in the sound and fury of the process.

So I was pleased to hear of a different kind of protest I saw on the television news a while back. Down in California (where else?) a restaurant was serving lion steaks to their customers at $100 a plate, which is about eighty bucks more than I would pay for any steak. So, my first reaction was, "Way to go!" No steak dinner is worth $100 a plate."

I happen to think that the cost of hamburger is too high, not to mention the cost of a hot dog at the game. Even so, I like hamburgers and hot dogs. But a slice of Simba?

As usual, I had missed the point. The protest wasn't against the high cost of lion steak. This crowd was complaining about serving the king of the jungle as the gourmet special. I guess there are certain things you just don't expect to see on the menu of your favorite restaurant: salamander toes, crabgrass soup, iguana livers, filet of lion, etc.

The thought also briefly crossed my mind that if a protest is in order cows have a lot more reason to be upset with restaurants than lions do. But you don't see crowds of protesters marching on Sizzler or Munch-A-Burger calling for the rescue of cows. Well, you may see demonstrators at the burger outlet, but they're probably in the Michele Obama Brigade against "unhealthy" food.

I don't have trouble, however, understanding why a few people would be upset about lion steak on a restaurant menu. What do they know? Everything they know about lions, they learned from Disney movies. After seeing The Lion King twenty or thirty times with my grandkids I realize how easy it is to forget that lions are predators. And lions, in their native habitat, feast on everything from stately zebras to unwary great, white hunters. I doubt if a lot of the folks out there demonstrating against the restaurant had seen The Ghost and the Darkness. This is a movie about a couple of lions doing some serious demonstrating of their own against the building of a long-distance railroad line in East Africa. There were several graphic scenes showing these two kings of the jungle terrorizing a railroad construction camp and snacking on slow-footed workers.

As I watched these up-scale, Beverly Hills protesters walking around in circles in front of the restaurant I thought to myself that at least they weren't smashing windows and setting fires. They were orderly, and some were carrying expensive-looking, stuffed, toy lions, but I began to wonder just how serious could they really be. They almost looked took cute.

No doubt it seems a bit objectionable to such people that a restaurant should carve up this lordly pussycat of the friendly Disney image solely for the dining pleasure of the upper classes. What was the purpose of this demonstration, then? To force lion meat off the menu? Rescue the reputation of the lion as the king of beasts? Whatever the reason, it seems to me that they were going about it all wrong.

Look, if you want to make lion-steak-eaters sit up and take notice, send in the lions to do the demonstrating.

I realize that all citizens have a right under the First Amendment to demonstrate, protest, march, and otherwise express their views in a peaceable and lawful manner. I support that. But sometimes I wonder if we haven't become such a nation of grumblers over everything with which we disagree that the change we think we're demanding is lost in the sound and fury of the process.

So I was pleased to hear of a different kind of protest I saw on the television news a while back. Down in California (where else?) a restaurant was serving lion steaks to their customers at $100 a plate, which is about eighty bucks more than I would pay for any steak. So, my first reaction was, "Way to go!" No steak dinner is worth $100 a plate."

I happen to think that the cost of hamburger is too high, not to mention the cost of a hot dog at the game. Even so, I like hamburgers and hot dogs. But a slice of Simba?

As usual, I had missed the point. The protest wasn't against the high cost of lion steak. This crowd was complaining about serving the king of the jungle as the gourmet special. I guess there are certain things you just don't expect to see on the menu of your favorite restaurant: salamander toes, crabgrass soup, iguana livers, filet of lion, etc.

The thought also briefly crossed my mind that if a protest is in order cows have a lot more reason to be upset with restaurants than lions do. But you don't see crowds of protesters marching on Sizzler or Munch-A-Burger calling for the rescue of cows. Well, you may see demonstrators at the burger outlet, but they're probably in the Michele Obama Brigade against "unhealthy" food.

I don't have trouble, however, understanding why a few people would be upset about lion steak on a restaurant menu. What do they know? Everything they know about lions, they learned from Disney movies. After seeing The Lion King twenty or thirty times with my grandkids I realize how easy it is to forget that lions are predators. And lions, in their native habitat, feast on everything from stately zebras to unwary great, white hunters. I doubt if a lot of the folks out there demonstrating against the restaurant had seen The Ghost and the Darkness. This is a movie about a couple of lions doing some serious demonstrating of their own against the building of a long-distance railroad line in East Africa. There were several graphic scenes showing these two kings of the jungle terrorizing a railroad construction camp and snacking on slow-footed workers.

As I watched these up-scale, Beverly Hills protesters walking around in circles in front of the restaurant I thought to myself that at least they weren't smashing windows and setting fires. They were orderly, and some were carrying expensive-looking, stuffed, toy lions, but I began to wonder just how serious could they really be. They almost looked took cute.

No doubt it seems a bit objectionable to such people that a restaurant should carve up this lordly pussycat of the friendly Disney image solely for the dining pleasure of the upper classes. What was the purpose of this demonstration, then? To force lion meat off the menu? Rescue the reputation of the lion as the king of beasts? Whatever the reason, it seems to me that they were going about it all wrong.

Look, if you want to make lion-steak-eaters sit up and take notice, send in the lions to do the demonstrating.

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

Book Signings

The first book signing events for "Charlie's Girl" have been scheduled. We will post others as information becomes available. Please check back for updates. Also check Mary-Helen's blog: http://ourwaywithwords.com

June 6 Deseret Book Store Henderson, Nevada 6:30-8:00 pm

June 8 Deseret Book Store St. George, Utah 2-4 pm

June 6 Deseret Book Store Henderson, Nevada 6:30-8:00 pm

June 8 Deseret Book Store St. George, Utah 2-4 pm

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

PERSPECTIVE

It's funny how you never end up where you thought you would, no matter which road you take. Way back there in high school, I thought things were pretty predictable, and that everything was much simpler than it turned out to be. I look back and think of all the roads not taken and wonder where and what I'd be if I had chosen a different fork. But I realize that in the end things are what they are. Maybe it's just as well that we don't know from the beginning how things will turn out. That makes sense to me now, and I'm sure it does to my friend, Carolyn, as well.

Carolyn and I had become good friends by the time I reached high school seniorhood. We had sort of grown up together, but I can't remember when we first met. It seems that I had known her forever. She had been on the fringes of my life at first, coming and going; close now, more distant at other times--present, but not an important part of my life. That came later, after I had spent years ignoring her while I hung out with her brother, Blaine, who was my best friend through those early adolescent years.

We weren't intentionally uncivil to Carolyn, Blaine and I, but boys and girls revolved around different suns at that age. Boys didn't have friends who were also girls. And, besides, Carolyn was the kid sister.

Although Blaine was a year older than I, we were almost inseparable during our school years, which means that I spent a lot of time at the Walker house. Carolyn's friends were girls then, and the things Blaine and I did held no interest for them. They were learning how to be girls in the games they played, and Blaine and I were busy learning to be boys.

The few times I did pay any attention to Carolyn was to aggravate her. That was Blaine's role as the older brother, and I sort of joined in as an unofficial member of the family. I'm convinced that boys are born with a gene, as yet undiscovered by medical science, which makes them pester girls until they reach the age of fifteen or sixteen. That's about the time all that other stuff kicks in, and the whole relationship changes.

Boys sort of sail through those early male-female acquaintances as if the things they say and do to girls will never come back to haunt them. Like the time Blaine and I walked into their living room and found Carolyn practicing her alt o clarinet. I took one look at that instrument and thought it was the strangest thing I had seen in all my life. She looked so serious trying to squeak out a tune that I couldn't help laughing.

"What's so funny, BB Brain?" she snarled.

"That thing. . .," I said, still snickering. "What is it? It looks like a pipe fitter's nightmare."

I don't know what I expected from her, but she appeared to have no sense of humor at all. She took the comment all wrong. There was something flashing in her eyes that should have warned me even before she came after me screaming like an incoming artillery round. "You want nightmares? I'll give you nightmares!"

She was mad enough to wrap her clarinet around my head. She might have done it, too, if she had been able to catch me. My lesson for the day: keep your comments to yourself around a serious musician, no matter what you think of the horn she plays.

That was the year that Carolyn joined Blaine and me in high school. It was an awkward time for me. I think it was for everybody, but maybe they were better at hiding it than I was. I went on for a while trying to ignore Carolyn, but I couldn't get away with it any more. All of a sudden one day, I noticed that she had developed a personality, and that we had a lot in common. And besides, overnight it seemed, she had become kind of cute. This I had never suspected during all those years of traditional boy-girl hostility. A whole new relationship began between us. Blaine even seemed to treat her differently. Maybe it had something to do with maturity, but from then on, Carolyn and I grew closer as friends.

After Blaine graduated from high school and joined the Air Force, Carolyn and I, left behind to finish our last years of high school, became best friends. We shared many of the same interests and enjoyed spending time together. On summer nights we sat on her family's front porch and talked until way too late to suit her parents.

We were full of dreams back then. It seemed to us that everything was possible, and that we had all the time in the world to do it. We talked often of going off to see the world, or being movie stars, of writing stories and singing songs. I might have been reluctant to admit it to the guys, but Carolyn and I even read poetry to each other.

On cool nights, or on summer evenings when the warm, honeysuckled breezes overcame us we would move inside and play Nat King Cole records for hours. Lost in mutual dreams of the limitless future, we said little as Mister Cole's mellow voice confirmed to us that all our dreams could come true. We were simply comfortable with each other in our innocence.

The time finally came, as it always must, to put some distance between dreaming and doing. I went off to college for a year. Carolyn stayed at home to finish her last year of high school. At the time I didn't think anything of it. I was sure she would follow her dreams sooner or later.

In the meantime I was learning that dreams can wait. College didn't do it for me. After a year I joined the Army, not to pursue a dream, but to fulfill a duty and to put on hold dreams that I now realize I was afraid of. I told Carolyn goodbye over the telephone. I could just see her shaking her head sadly as she wondered what had happened to the dreamer.

I didn't get home very often over then next several years, but I did meet my future wife and we were married a few months later. Building our new life together took us across the country and back, then back across the country again, this time to Arizona. I became a history professor, and my teaching assignments have taken me half way around the world.

It was fifteen years before I got back home for a visit. I found almost everything changed, not all for the better, but the good things seem to remain constant. I talked to Carolyn on the telephone. We spoke warmly, and a little sadly, about the old days. She said to me, "I was talking with one of my friends the other day. I told her that when I was a teenager my best friend was a boy, and how we used to be so close. Do you remember the things we did and how many dreams we had?"

"Yes, I remember," I said. "It seems so long ago."

"You remember all that?" she asked with some surprise. Maybe she hadn't expected that it would be so clear to me, too.

A trunk-full of memories swirled through my head in a split second. I could almost sense the anticipation I had felt all those years ago when the whole world lay before us. But it was tempered with the knowledge that I had left those dreams, or the way I had dreamed them, at least, back there on the Walker's doorstep.

I half expected her to say something about foolish youth and dreams giving way to reality. She surprised me. "Well," she said, "you've sure made a lot of your dreams come true."

"Me?" I couldn't hide my astonishment at her comment.

"Yes. You. You got away from here. You've traveled around the world. I'll bet you've seen all those places we used to talk about."

"Some of them," I said.

I had been to many of the places that to us had seemed as distant and mystical as Camelot or Oz; places whose names sounded like a wizard's incantation--Singapore, Rangoon, Kuala Lumpur, the Volga. But I had accepted everything in my life as a matter of course, never realizing just how special and miraculous it had all been in reality. Carolyn and I used to talk about putting Gaffney behind us as if all the wonder lay out there somewhere beyond the small, cotton-mill hometown that had been the limits of our world.

Well, she was right. I had gone to see the world. But it hadn't happened the way I had dreamed it. There had been no crusades, no dragons to slay, no great victories. What I saw as a very normal, day-to-day existence had led me through what, in fact, had been a pretty exciting and fulfilling life.

"I guess I have done a lot of things, but most of them weren't planned," I said. "Maybe that's the way life is, after all."

"You really believe that." She said it as a statement rather than a question.

"I guess so," I said. "Maybe if you wait long enough for something to happen, it will."

"I don't think so," she said. "I waited."

Carolyn and I had become good friends by the time I reached high school seniorhood. We had sort of grown up together, but I can't remember when we first met. It seems that I had known her forever. She had been on the fringes of my life at first, coming and going; close now, more distant at other times--present, but not an important part of my life. That came later, after I had spent years ignoring her while I hung out with her brother, Blaine, who was my best friend through those early adolescent years.

We weren't intentionally uncivil to Carolyn, Blaine and I, but boys and girls revolved around different suns at that age. Boys didn't have friends who were also girls. And, besides, Carolyn was the kid sister.

Although Blaine was a year older than I, we were almost inseparable during our school years, which means that I spent a lot of time at the Walker house. Carolyn's friends were girls then, and the things Blaine and I did held no interest for them. They were learning how to be girls in the games they played, and Blaine and I were busy learning to be boys.

The few times I did pay any attention to Carolyn was to aggravate her. That was Blaine's role as the older brother, and I sort of joined in as an unofficial member of the family. I'm convinced that boys are born with a gene, as yet undiscovered by medical science, which makes them pester girls until they reach the age of fifteen or sixteen. That's about the time all that other stuff kicks in, and the whole relationship changes.

Boys sort of sail through those early male-female acquaintances as if the things they say and do to girls will never come back to haunt them. Like the time Blaine and I walked into their living room and found Carolyn practicing her alt o clarinet. I took one look at that instrument and thought it was the strangest thing I had seen in all my life. She looked so serious trying to squeak out a tune that I couldn't help laughing.

"What's so funny, BB Brain?" she snarled.

"That thing. . .," I said, still snickering. "What is it? It looks like a pipe fitter's nightmare."

I don't know what I expected from her, but she appeared to have no sense of humor at all. She took the comment all wrong. There was something flashing in her eyes that should have warned me even before she came after me screaming like an incoming artillery round. "You want nightmares? I'll give you nightmares!"

She was mad enough to wrap her clarinet around my head. She might have done it, too, if she had been able to catch me. My lesson for the day: keep your comments to yourself around a serious musician, no matter what you think of the horn she plays.

That was the year that Carolyn joined Blaine and me in high school. It was an awkward time for me. I think it was for everybody, but maybe they were better at hiding it than I was. I went on for a while trying to ignore Carolyn, but I couldn't get away with it any more. All of a sudden one day, I noticed that she had developed a personality, and that we had a lot in common. And besides, overnight it seemed, she had become kind of cute. This I had never suspected during all those years of traditional boy-girl hostility. A whole new relationship began between us. Blaine even seemed to treat her differently. Maybe it had something to do with maturity, but from then on, Carolyn and I grew closer as friends.

After Blaine graduated from high school and joined the Air Force, Carolyn and I, left behind to finish our last years of high school, became best friends. We shared many of the same interests and enjoyed spending time together. On summer nights we sat on her family's front porch and talked until way too late to suit her parents.

We were full of dreams back then. It seemed to us that everything was possible, and that we had all the time in the world to do it. We talked often of going off to see the world, or being movie stars, of writing stories and singing songs. I might have been reluctant to admit it to the guys, but Carolyn and I even read poetry to each other.

On cool nights, or on summer evenings when the warm, honeysuckled breezes overcame us we would move inside and play Nat King Cole records for hours. Lost in mutual dreams of the limitless future, we said little as Mister Cole's mellow voice confirmed to us that all our dreams could come true. We were simply comfortable with each other in our innocence.

The time finally came, as it always must, to put some distance between dreaming and doing. I went off to college for a year. Carolyn stayed at home to finish her last year of high school. At the time I didn't think anything of it. I was sure she would follow her dreams sooner or later.

In the meantime I was learning that dreams can wait. College didn't do it for me. After a year I joined the Army, not to pursue a dream, but to fulfill a duty and to put on hold dreams that I now realize I was afraid of. I told Carolyn goodbye over the telephone. I could just see her shaking her head sadly as she wondered what had happened to the dreamer.

I didn't get home very often over then next several years, but I did meet my future wife and we were married a few months later. Building our new life together took us across the country and back, then back across the country again, this time to Arizona. I became a history professor, and my teaching assignments have taken me half way around the world.

It was fifteen years before I got back home for a visit. I found almost everything changed, not all for the better, but the good things seem to remain constant. I talked to Carolyn on the telephone. We spoke warmly, and a little sadly, about the old days. She said to me, "I was talking with one of my friends the other day. I told her that when I was a teenager my best friend was a boy, and how we used to be so close. Do you remember the things we did and how many dreams we had?"

"Yes, I remember," I said. "It seems so long ago."

"You remember all that?" she asked with some surprise. Maybe she hadn't expected that it would be so clear to me, too.

A trunk-full of memories swirled through my head in a split second. I could almost sense the anticipation I had felt all those years ago when the whole world lay before us. But it was tempered with the knowledge that I had left those dreams, or the way I had dreamed them, at least, back there on the Walker's doorstep.

I half expected her to say something about foolish youth and dreams giving way to reality. She surprised me. "Well," she said, "you've sure made a lot of your dreams come true."

"Me?" I couldn't hide my astonishment at her comment.

"Yes. You. You got away from here. You've traveled around the world. I'll bet you've seen all those places we used to talk about."

"Some of them," I said.

I had been to many of the places that to us had seemed as distant and mystical as Camelot or Oz; places whose names sounded like a wizard's incantation--Singapore, Rangoon, Kuala Lumpur, the Volga. But I had accepted everything in my life as a matter of course, never realizing just how special and miraculous it had all been in reality. Carolyn and I used to talk about putting Gaffney behind us as if all the wonder lay out there somewhere beyond the small, cotton-mill hometown that had been the limits of our world.

Well, she was right. I had gone to see the world. But it hadn't happened the way I had dreamed it. There had been no crusades, no dragons to slay, no great victories. What I saw as a very normal, day-to-day existence had led me through what, in fact, had been a pretty exciting and fulfilling life.

"I guess I have done a lot of things, but most of them weren't planned," I said. "Maybe that's the way life is, after all."

"You really believe that." She said it as a statement rather than a question.

"I guess so," I said. "Maybe if you wait long enough for something to happen, it will."

"I don't think so," she said. "I waited."

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

CHARLIE'S GIRL

Charlie’s Girl

By

Mary-Helen and Daniel Foxx

CHAPTER ONE

The dusty, gray Ford swayed into the driveway of the bus station parking lot and jerked to a stop straddling the two remaining parking spaces. Muriel Dobson and her friend, Grace Matthews, sat and fanned themselves to help stir the meager breeze while they waited for the arrival of the 4:50 from Atlanta. On the back seat a chubby, red-haired boy lounged while he read comic books and noisily munched peanut brittle while his mother’s droning voice rose up on the hot air.

“…So I told Mark William, I said, ‘You just come on along with me. Miz Matthews can use your help with the baggage, and it’ll keep you busy and out of trouble for the rest of the afternoon.’”

The boy winced imperceptively at his mother’s words and wrinkled his freckled nose into a copper-colored blotch.

“My land! You never saw a boy that could find so much trouble to get into! My girls never gave me a minute’s bit of worry compared to this one! He’s a caution! I can’t wait for school to start up again, so I can get some peace of mind. I always did think those summer vacations were too long.”

Mark William’s mother shifted under the steering wheel to stretch her huge legs out before her against the floorboard. She smoothed her skirt and looked across the seat at her friend who sat staring out the window. Enviously she considered the other woman’s appearance.

Grace Matthews was at least ten years older than she, yet they seemed almost the same age. Grace hadn’t had an easy life, but it certainly didn’t show in her face, which had only softened with age. Her figure was just slightly thickened, but then she’d only had one child, not four as had Muriel. Grace’s long hair, still more brown than gray, looked as though it had been professionally streaked down at Myra’s beauty shop. She wore it pinned up into a mound high on her head, but wisps of it escaped and tightly coiled themselves into little ringlets at the nape of her neck. She wore a trim-fitting green dress of her own making which heightened her quiet loveliness. Her eyes were a mystery-clouded hazel, from which even her simple, wire-rimmed eyeglasses could not detract.

It didn’t seem fair, somehow, for a woman to look that good at her age. The driver turned her gaze to her own huge lap before her, and compared herself to her friend.

Muriel was sixty-five pounds overweight and looked perpetually tired, her gray hair ill concealed with a thin rinse. She looked much older than she really was. Her last child, that imp in the back seat who had come to her late in life after her other three children were all grown, was responsible for every last gray hair.

Perhaps she had been too old to have another child after her patience was all used up, and just when she could have been free to travel more with her husband, Luther, to all his furniture shows. The store was doing well then and they could have left things to run themselves long enough for a nice little vacation now and again. Maybe then things would have been different, she thought bitterly.

The red-haired boy squirmed restlessly on the seat, his face dripping with perspiration. This unusual heat wave had held the small South Carolina piedmont town of Grayson in its grip for two long miserable weeks. Mark William longed to escape the car in search of a breeze.

Across the way old Will Perkins sat in his usual place, with his chair tipped back against the depot wall, and whittled away the time on a piece of poplar. The boy watched the shavings pile up on the ground until he could bear it no longer. He reached for the door handle as quietly as he could and eased the door open.

“I’ve been in hot weather, but I’ve never seen anything like it in my life. They’ll probably call this the great heat wave of nineteen and sixty four,” Muriel complained, mopping her brow and neck with a handkerchief. Then catching a glimpse of movement from the corner of her eye she said without breaking stride in her conversation, “Just where do you think you’re going, young man?”

“I’m just gonna sit over there in the shade where I can watch for the bus, Mama. I won’t go no where else,” the boy whined.

He was already half way across the parking lot before he slowed down for her reply, but when it didn’t come, he picked up his pace. Once his mother had a captive audience, she never stopped talking long enough to pay him much mind.

He sat down beside the old man, who never even looked up. Will Perkins was as deaf as a post and didn’t have much to say to anyone. Perhaps that was why the boy enjoyed; no, craved, his company. Will’s silence was golden. The boy looked toward the car, but he could only just faintly hear his mother’s crescendo drifting from the open car windows. Glancing back he could see Mrs. Matthews nodding politely or shaking her head absently while obviously pretending to hear every word.

“But as I was telling the pastor just last week…or was it the week before?” She worried over the date, and then continued confidently. “No, I’m sure it was last week because it was right after the benediction at prayer meetin’. So I said to him, I says, ‘You know, Reverend Rollins, you just don’t know how hard it is to get enough tenors to come out to choir. We have a gracious plenty of sopranos, and goodness knows, we have enough altos. But all the men want to sing bass.’”

She slowed up for breath and her companion took advantage of the pause to ask, “Muriel, what time do you have? My watch has stopped. It must be getting close to five o’clock, isn’t it?”

Muriel Dobson looked at the watch, it’s expansion band strangling her fat wrist, and slid it downward to ease the circulation. “Why, yes it is, honey. It’s two minutes to five right now. I’ve never known that bus to be on time though. Well, anyway, I says to him, I says, ‘I hate to say it, Reverend, but if you’d just speak to…’”

While Mrs. Dobson continued her story, Grace sat with hands folded in her lap, resigned to waiting. Just then the huge, gray and blue bus loomed at the corner and swerved into the station parking lot.

Muriel exclaimed, “Well, there it is now, and not a minute too soon either. We’ll have to really hurry to make it to church this evening. I’ll just wait for you here, Grace, so you can hurry faster. Just holler out to Mark William to get over there and help you with the bags when you’re ready. Mark William,” she bawled, “you help her with those bags when she’s ready. You hear me?”

Grace climbed out of the car and slowly approached the station. She watched each passenger that got off the bus, waiting for a young girl she had not seen since she was a baby. Her pulse quickened. She had seen no recent pictures of her fourteen-year-old granddaughter and had received no description, but she felt confident she would know her son’s child immediately.

Finally, a slight figure of a girl stepped off the bus. She was dressed in a faded skirt and blouse and grubby, white sneakers with no socks. Her little toes pushed out through the fraying canvas of the shoes. Her long, thick, dark hair was worn in two loose ponytails and cascaded down her rather undeveloped chest. This couldn’t be the object of her search, Grace decided, for this girl couldn’t be more than twelve years old at the most. The last passenger had gotten off the bus now, and the driver was unloading the baggage compartment. The girl stood only a few steps from the bus and stared at her strange surroundings. Grace noted that she seemed nervous and ill at ease. There seemed to be something vaguely familiar about her in an unsettling sort of way.

“Are you Rosalind?” Grace asked with doubt in her voice as she searched the young girl’s face for some sign of recognition. But there was none, just a blank expression that greeted her. How strange. She’d always pictured her granddaughter as a blond.

“Yes, and you are…” the girl hesitated for words.

“I’m Grace Matthews. I’m your grandmother,” the older woman said a little too stiffly.

Rosalind didn’t know what to do next. Should she offer to shake hands, or should she kiss her? But the woman didn’t seem to encourage either. Instead, she turned abruptly and addressed her attention to the driver as he took the last suitcase from the belly of the bus. Taking the baggage check from the girl’s hand, Grace handed it to him and waited while he searched for the bag.

“It’s a red, plaid suitcase, a small one,” the girl offered.

“I’m sorry, Ma’am, but it’s not here. It must have been on that second section out of Phoenix. It’s bound to turn up. Maybe you ought to check tomorrow when the station’s open.” He seemed anxious to be on his way and climbed back up the steps to his driver’s seat, leaving the flustered girl to follow in the wake of her grandmother, who had headed for the parking lot.

“It’s insured, isn’t it, Rosalind?” Grace spoke over her shoulder.

The girl halted in her footsteps and stammered, “I don’t know. I mean…I guess so…Don’t they always? Well, I almost missed the bus, and they kept saying to just hurry up, and I didn’t think to…” her voice trailed off when she saw Mrs. Matthews’s stare.

“You mean you didn’t buy extra insurance for it when you got your ticket? They only insure the bags for twenty-five dollars each, and that would hardly replace a suitcase nowadays, much less all your clothes.”

The woman was clearly exasperated and didn’t try to conceal her annoyance, but the girl was so chagrinned that Grace decided it would be best to drop the subject for now.

Mark William, who had been careful to stay out of sight until now that he was sure there was no bag to carry, raced over to the car to dutifully open the door for Mrs. Matthews. With an admiring grin he noticed that the girl was about his height, even if she was older. Grace paused to indicate the back seat for Rosalind and then eased into the car.

“Muriel, this is my granddaughter, Rosalind.” She turned toward the back seat and continued, addressing the girl, “and this is our choir director, Miz Muriel Dobson, who was kind enough to drive me down here to meet you. And this is her son, Mark William Dobson. They’re our neighbors.”

Rosalind looked out of dark brown eyes and mumbled a quiet but appropriate response, quickly lowering her gaze. It was difficult for her to look people in the eye for very long.

Muriel appraised her thoughtfully and said, “So, you’re Charlie’s girl.” Then, staring into the rear view mirror as she started the car’s engine, she continued, “Can’t say you look much like your father. He was always such a good-looking young man with those gorgeous blue eyes. My daughter, Mary Louise, used to say he was the best looking boy in Grayson. She always did have a crush on him ever since they were little. You remember that, don’t you, Grace?”

Mrs. Matthews nodded slightly, her lips pursed together, as the car backed out of the parking lot. She stared straight ahead through the windshield as Muriel pursued the subject of Charlie’s blond hair and sun-tanned good looks and his popularity. Rosalind self-consciously tossed her ponytails back over her shoulders. She knew she wasn’t pretty and was still stinging from the heavy-set woman’s comparisons to her father.

“…still, she didn’t do too bad marrying Howard from over to Spartanburg,” Muriel rattled on about her daughter as the old sedan lumbered down the streets of town. Almost everyone in Grayson knew that Mary Louise had set her cap for Charlie early on, and had had a fit when he up and married someone else. Not that the feelings on Charlie’s part had ever been mutual. But Muriel was relieved when Mary Louise’s marriage to Howard had worked out, despite fears that she had just married him on the rebound.

Rosalind quickly surmised that here was a woman who could talk on automatic pilot and did not seem to mind or even notice if she had lost her audience. The girl stole a quick sideways glance at the freckled-faced boy who sat staring at her. She shifted her position slightly and spread her hand out on the seat beside her. Under her hand was something wet and sticky. She recoiled slightly to notice a big, wet, partially eaten plank of peanut brittle on the seat where her hand had been.

“Oh, thanks!” the boy exclaimed as he reached greedily for the remnant of his treat.

The two women in the front seat were for the moment ignoring the little peanut brittle drama going on in the back seat. They chattered about the upcoming church supper; or rather Mrs. Dobson chattered while Mrs. Matthews mostly listened and nodded occasionally, but unnecessarily. Grace’s forbearance was more than polite. It came from years of close friendship. Few people were as patient with Muriel as Grace was.

“You know, there’s not much time left. Maybe we ought to just stop off and get a sandwich so we’ll be able to get to the church by six forty-five,” Muriel prompted.

“That’s a good idea, but only if you’ll let me buy. It will pay for the gas,” Grace offered.

After putting up a weak argument, Muriel acceded to her friend’s suggestion, as Grace knew she would. A block further on she pulled off at the Tastee Freeze.

“Why don’t ya’ll give me your orders and Rosalind and I can carry everything,” Grace suggested.

“That’s a good idea. I’ll have a barbeque with iced tea. What’ll you have, Mark William, and don’t make a pig of yourself.”

“I want a cheeseburger with chili and mayonnaise and a cherry Coke,” the boy said as he scrambled over the front seat. “I can come with you to help carry everything.”

“Oh no, you won’t! You’re gonna sit right here in this car where I can keep an eye on you. None of your tricks like last time. Unscrewin’ the salt and pepper lids! Now git back over that seat and mind me!”

Grace closed the car door and said, “We’ll just be a minute. It doesn’t look too crowded.”

As they waited at the take-out window, Mark William leaned over the front seat and asked, “Why is she comin’ here to live with Miz Matthews? Where’s her own folks?”

“She’s been livin’ in Arizona with foster parents. You remember, I told you. Her mama and daddy died. Now don’t be so nosy. They’re gonna hear you.” Muriel shushed him, though her own voice was much louder than his.

Minutes later Grace and Rosalind returned with the bags of greasy food. They all ate quickly with little conversation, even from Muriel, and soon they were on their way. Rosalind gazed out the window at the passing scenery. She was awed by the canopy of trees arching over the streets. They turned a corner and pulled over to the curb in front of a white, frame, two-story house.

“If you don’t mind,” Muriel said, “I’m gonna just drop you off and head on over to the church. I’m sure you two have a blue million things to talk about, and I can see you later after prayer meetin.’” She said all this without a single breath. “Bye-bye, now. Don’t be late.”

She pulled away as soon as her passengers had closed their doors behind them, and Rosalind followed her grandmother up a sidewalk flanked by concrete benches. They climbed the steps and Grace paused to check the mail in the box mounted on the porch wall below the house numbers, 406. Finding nothing in the box, she removed her house key from her purse, unlocked the front door, and went inside.

Rosalind followed in her wake staring into the unfamiliar room as Grace switched on the light and laid her purse on the hall table beside the staircase. They each missed the mindless chatter of Muriel Dobson and were aware of the awkwardness of their first meeting. Grace ran her gloved finger across the table to test for dust and glanced about her home approvingly.

When her husband, Sam Matthews, passed on in 1952, he left her this house, a small insurance policy, and just enough money for Grace to live out her life comfortably. But now that life was to include this adolescent girl who was so reticent as to seem almost rude. Grace still wasn’t sure she welcomed this intrusion upon her quiet widowhood, but with a sigh she acknowledged that the decision had already been made.

“Why don’t I show you your room upstairs and you can freshen up in the bathroom. It’s a shame your suitcase isn’t here, but that outfit will have to do for church tonight.” She eyed Rosalind critically, marking the tennis shoes with distaste, then turned and led the way upstairs as the girl meekly followed.

“We’re going to church tonight?” Rosalind asked in amazement.

“Yes, dear. Didn’t you attend church in Arizona?”

“Well, yes. Sometimes. But never on Wednesdays.”

“It’s prayer meeting tonight, and I’m anxious to have everyone meet you.”

With a sting of conscience Grace realized that that was a lie. Her feelings were just the opposite. She tried not to pay too much attention to the girl’s rag-tag looks. What would people think? She recalled her son’s well-groomed appearance. In despair she thought to herself, Muriel was right. She doesn’t look a bit like Charlie.

Late that night Rosalind lay awake in the large bed thinking over the day’s events. The strangeness of the dark, old house bore down upon her, but somehow it felt a bit friendlier than most of the other houses she had slept in over the past few years.

Her teeth hurt. They were still on edge from having ridden for three days and nights with her head propped on a pillow against the bus window. It wasn’t a bad trip though, despite the discomfort and exhaustion. In some places the new scenery was exquisite and almost never boring. She had imagined that she was free of everything, rushing toward the end of the rainbow. But during the last leg of her journey she had had nagging worries over the prospect of meeting her new guardian. Up until two weeks ago Rosalind had known nothing of the little South Carolina town where her father had been born, and now she was to live there with his mother. Now. After all these years.

The social worker hadn’t given her much information about Grace Matthews. She told the girl that her parents had been killed in an auto accident north of Phoenix when she was only a toddler; and that she had somehow survived the crash because she had rolled off the back seat to the floorboard in her sleep. Some flying object in the car had struck her unconscious, and by the time she had regained consciousness weeks later, the funeral arrangements had been carried out and a foster family was to take her into their home. She was now a ward of the state.

Her first foster parents had tried to be kind, but they had problems of their own. Then when the husband left the family the wife had to go to work to support her own four children. Thus Rosalind entered the foster care rat race, bounced from one foster home to another for years, until this summer when word came that her grandmother had traced her whereabouts and asked to have custody. So Rosalind had boarded a Greyhound bus in Phoenix and crossed the country to the Southland where she was to live with yet another stranger. Why, she wondered, after all this time? She only knew that her grandmother had been very ill for several years following the accident, and had been unable to provide a home for her any sooner. Funny, Rosalind thought, she didn’t look like she’d been sick a day in her life.

Rosalind rose from bed and crept silently to the window. She sat on the window seat and watched the stars flickering through the trees. Real trees that towered skyward! In Arizona, people planted cacti in their desert lawns, or mulberry trees that looked like oversized umbrellas that had been struck by lightning. Most of the mature trees were kept in parks or on golf courses, like pets. Everything looked so green here, even with the heat. She smiled at the thought of everyone complaining about how hot it was. While it was awfully humid here, the heat was nothing to compare with that of a Phoenix summer. She thought of her last home in the suburbs of the city and of trying to keep cool in the hot, crowded little house.

Her thoughts wandered back to the present and she decided this was going to be just like all the other times, getting used to another family. She wasn’t sure this home would end up any differently from the rest. It wasn’t that she had meant not to fit in. She wanted a home – needed a home – more than anything. But she had had terrible night terrors when she was younger, and would jump out of bed to run screaming through the house in the middle of the night, eyes glazed. She couldn’t recognize her surroundings or anyone about her, and if people tried to wake her up, she would stare right through them, shrieking as though they were terrible creatures from her nightmares. These episodes continued for as long as half an hour before she could be brought out of them and put back to bed; and they often reoccurred several times a night. Small wonder her foster parents were distraught and probably never considered being anything more permanent. Luckily they were part of a social program as foster parents, and could call upon the rest of that system for help, and a county psychologist had had a talk with her and learned that her nightmares were always the same.

She was walking through an old cemetery alone at night. People began staring at her from behind trees and gravestones. One by one they would follow her or spring up in her path, their faces changing to ghoulish, hideous things right before her eyes. The dream occurred frequently with little variation. The doctor decided it was a manifestation of her having seen too many monster movies at an impressionable age, and probably relating her concept of death to the violent deaths of her parents. After counseling the dreams subsided for a time, but she retained a morbid fear of the dark. She would often sit up in her bed with her back to the wall the whole night through, staring at the fleeting night shadows in the room.

Small wonder she seldom lasted more than a few months in any one foster home, except for the year she had spent with a schoolteacher and his wife. She had liked that home best. Mrs. Jarnigan had really spent a lot of time with her. But then they adopted a baby and Rosalind’s stay came to an end. That was the nicest home she had lived in. She’d had her own room and was able to learn to play the piano, a little. Mrs. Jarnigan said she thought Rosalind had a real gift for music.

Rosalind closed her eyes and tried not to think of her years in foster homes. They had been such unhappy times, times when she wondered if she would ever really belong anywhere. Her experiences had made it difficult for her to make friends, to form attachments, to love people. Eventually she found she even preferred the frequent moves and changes in surroundings. At first she looked forward to going to what she hoped would be a real home; then after awhile she became restless again. Perhaps that was what made her uneasy about this latest move. Suppose she failed here too? There would be no place to move on to. The permanence of this arrangement frightened her.

She looked about the bedroom. A dim light from the small lamp on the dresser cast a warm patina over the furniture. This was the guest room and it was quite large. There was a big four-poster bed with a yo-yo bedspread folded neatly at the foot. An unbleached muslin dust ruffle brushed the soft carpet. The furniture was older, probably family antiques. She got up and walked around the room absently pausing to touch the chair, to run her hand across the headboard of the bed. There was even a fireplace, long since bricked up, probably when a furnace was installed. On the mantle were knick-knacks and pictures in ornate frames. They intrigued her. She stared at them in the dim glow of the night light and of the street lamps from outside, trying to find something, someone, who might answer all her questions. But there was nothing there for her. The eyes of strangers stared back. Judging by the clothing they wore, these images were captured many years ago.

All her life Rosalind had wondered who she was. All she had was her name. That, and a slim file folder in a neglected filing cabinet in Phoenix. All her life she had wondered. But now, now that she was here with someone who claimed to be her grandmother, here in the house where her own father grew up, she felt just as lost, just as alone as she ever had. What’s more, she wasn’t even sure her grandmother liked her. They certainly hadn’t seemed to hit it off very well so far. Even the way her grandmother had reluctantly offered the loan of a nightgown was a silent condemnation of her actions in the suitcase incident. Rosalind had accepted the gown, but it felt foreign to her. After hanging her rumpled skirt and blouse on a hook in the closet she had climbed into the big bed in her slip and pulled the sheets up to her neck. Even in this heat she needed the covers for security. For a few moments the sheets felt cool to the touch, but she soon kicked them back and lay there in the large bed.

“I’m glad she didn’t kiss me,” she told herself. “She’s just another stranger. I don’t know why I thought it would be any different here. Just because she says she’s my grandmother doesn’t mean she has to like me.”

She turned over on her side and pulled the covers over her head, leaving only enough room to breathe. She felt as if she wanted to cry, but tears wouldn’t come. It had been years. Besides, it never did any good. She lay there twisting a lock of her long hair around her finger late into the night.

Somewhere in the twilight zone between sleep and wakefulness, she saw the many faces of her foster parents. Some were kind; some were indifferent. Some were affectionate. Some were only interested in the monthly income she represented to them from the state. None were her parents. How many times she had wished someone would adopt her and take her away from all the unhappiness, the uncertainty; but the chances of this happening grew slimmer with each passing year. Everyone wanted a cute, cuddly baby to hold and love. No one wanted a child with emotional problems who didn’t know how to love, who didn’t want to.

The sun had risen and most of Grayson was deeply involved in its morning routine when Rosalind awoke to the sound of a blaring radio from the house next door. A familiar voice yelled out, “Mark William Dobson, you shut that radio off! Do you hear me?”

Rosalind threw back the covers and lay in the bed a few moments trying to absorb her surroundings in the daylight. The pale pink wallpaper was very out-dated but pretty in its own way; but Rosalind hated pink. Almost all her clothes were pink; all her hand-me-downs and garage sale specials. That color had come to symbolize her loneliness. No one spent much money on a foster child; not with the kind of turnover they had. She hoped her suitcase would never turn up. It was as wicked a thought as she had ever dreamed, and it was delicious. Her grandmother had said she would buy her some new clothes today if the suitcase hadn’t shown up at the bus station. She hoped so. The styles here seemed so much dressier than in the West.

She thought of the prayer meeting last night in the big, old, brick church on Main Street, and of the brief introduction she’d had to her grandmother’s friends and acquaintances. Mrs. Dobson was there, of course, and Mark William. She’d been introduced to several of the girls her age, including the two who sat in the pew in front of them. Stephanie and June had been cordial enough to Mrs. Matthews, and promised to take Rosalind to their Sunday school class the next Sunday. But their eyes didn’t miss her attire, and they whispered to themselves and giggled and passed notes during the service.

Mark William waved once from where he was sitting on the other side of the sanctuary. When he knew his mother’s back would be turned to him during the choir’s number, he had slipped out with such an accomplished maneuver that Rosalind was sure he was well practiced in such escapes. With the same skill he had managed to sneak back in unnoticed just before the benediction.

After the service the minister had shaken Rosalind’s hand and welcomed her to Grayson. He asked her where her home church was. She was too embarrassed to say she didn’t really have one since she had moved around so often. She didn’t want to admit that she had never joined a church. Why, she didn’t even own a Bible. When she lived with church-going people, she went wherever they went, whether Baptist, Methodist, Catholic or Assembly of God. She’d had no formal religious training, but she couldn’t admit all that to this dignified minister of the gospel.

Her grandmother answered for her with determination, “Rosalind’s father was born and reared here. This is her home church.”

The other girls hung back in a group, staring at Rosalind and whispering, pressing Stephanie and June for information. She was an outsider to them, even if she was a grandchild of the Matthews family, pillars of this church, and all that. As far as they were concerned, she would have to earn her way into their society.

A knock on the bedroom door brought Rosalind back to the present.

“Yes?” Rosalind said.

Her grandmother spoke through the door, “Wake up call.”

Rosalind sat on the side of the bed until she heard her grandmother’s voice again.

“Ready for breakfast?” Grace called from downstairs “I made pancakes and sausage since I didn’t know what you liked. Come on down as soon as you can, while they’re still hot.”

“I’ll be right there,” Rosalind answered as she scrambled out of bed and dressed hurriedly in the same outfit she had arrived in.

She didn’t want to get off on the wrong foot again so she carefully made the bed, pulling the yo-yo bedspread up over the pillow and tucking it in. The threads were old and broke between some of the circles of colored fabric. She bit her lip and tried to camouflage breaks in the bedspread threads with the throw pillows.

Standing in front of the dresser mirror she combed out her long hair, lifting it up into a ponytail and securing it with a rubber band. Staring at her image critically, she took a deep breath, opened the door, and left the room.

Rosalind descended the stairs and paused in the hallway to get her bearings. This was a marvelous old house built in a style that history buffs would appreciate for all the right reasons, which for the moment escaped her. But she was impressed with the security and strength it suggested. Typical of many old Southern homes, the hall bisected the first floor with rooms off to either side. You could see straight through to the back door and the kitchen was just off to the right at the end of the hall. The aroma of sausages and pancakes and hot coffee met her as she reached the end of the passageway.

She seated herself opposite her grandmother at the small kitchen table, and after Grace had asked the blessing, she helped herself to the delicious food.

“Did you sleep all right?” Grace inquired politely.

“Yes, thank you,” Rosalind lied. “The room is very big. Very nice,” she corrected herself. She should have said that she was not used to such a large room. She had never had so much space to herself before. The bedrooms in most of her foster homes were small and usually shared with other children.

“I called the bus station as soon as it opened, and your suitcase still hasn’t turned up. They’ve put out a tracer on it, but who knows how long it will take to locate it. We’d better plan to shop for you in town this morning. With school starting in a week you’ll be needing a lot of things.”

Rosalind responded politely, “Yes ma’am. Thank you.” Self-consciously she slowly ate her breakfast, remembering to chew with her mouth closed and mind her table manners.